Place

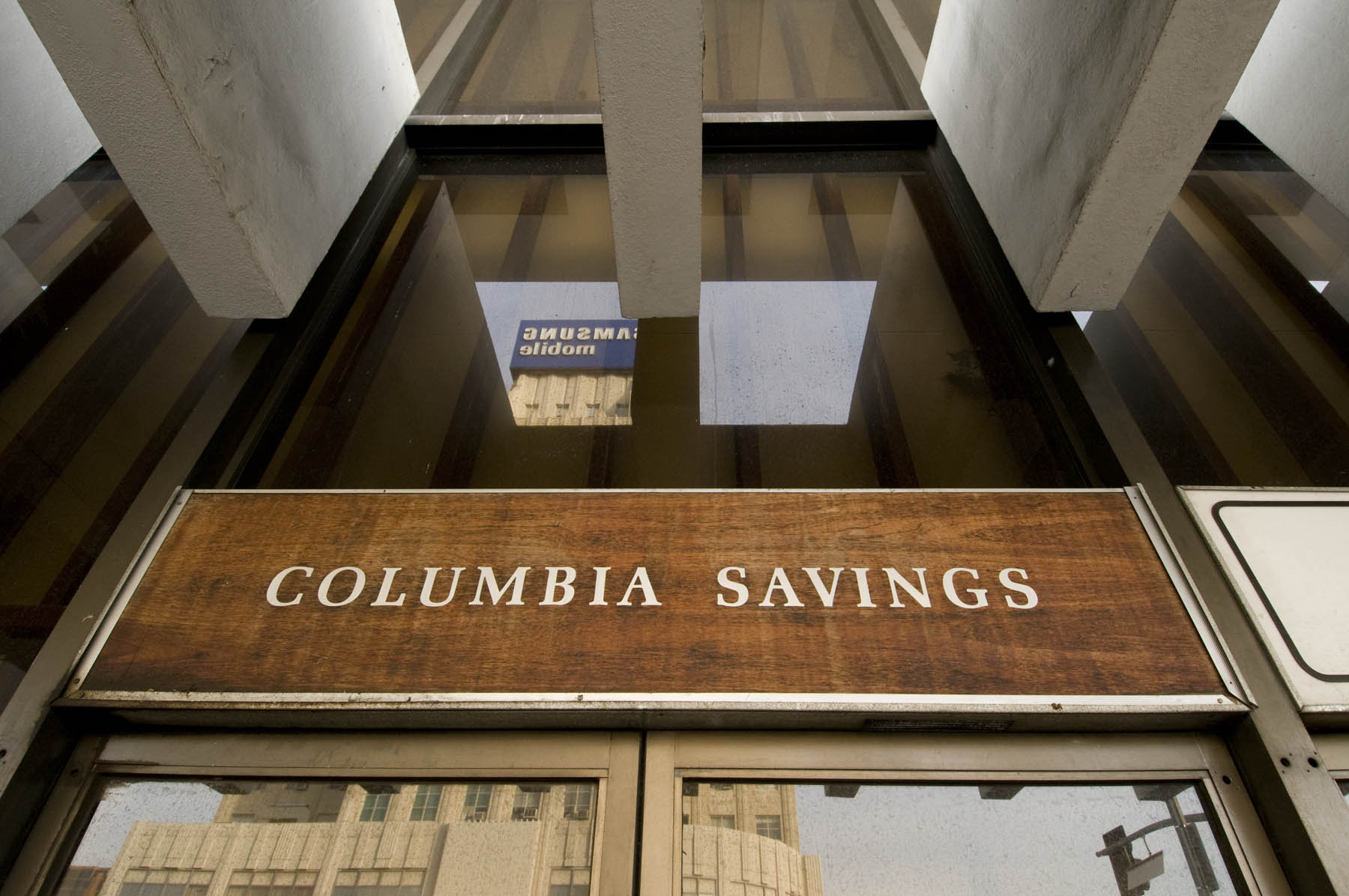

Columbia Savings (Demolished)

This striking building was designed by architect Irving Shapiro, completed in 1965, and demolished in 2010.

This striking building was designed by architect Irving Shapiro, completed in 1965, and demolished in 2010.

Place Details

Address

Architect

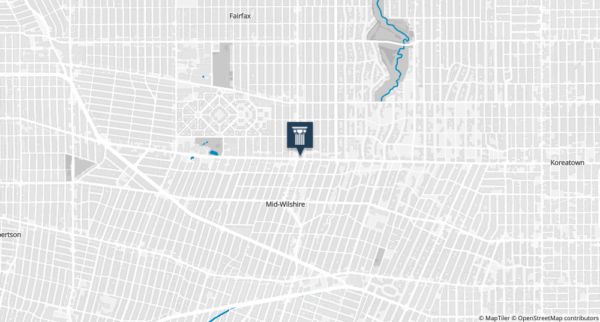

Neighborhood

Year

Style

Decade

Property Type

Government Officials

Community

Columbia Savings | Julius Shulman; Copyright J. Paul Getty Trust, The Getty Research Institute

Overview

The 1965 Columbia Savings building on the Miracle Mile was demolished in January 2010 despite an intensive preservation effort. The building was an important example of postwar bank design as well as the innovative integration of art and architecture. Most recently, the building had served as Wilshire Grace Church.

This issue underscores the plight of buildings from our recent past that are not yet fully understood or appreciated. The Conservancy and our Modern Committee are working hard to build awareness of our rich legacy of 1960s architecture, but we clearly have far to go.

About This Place

About This Place

The Columbia Savings building was designed by architect Irving Shapiro and completed in 1965.

The result of a design competition for the new Home Office of Columbia Savings and Loan Association, Shapiro’s winning design was selected over competing entries from Charles Luckman Associates and the Bank Building & Equipment Corporation of America.

The iconic building was profiled in the prestigious French architecture journal L’architecture d’aujourd’hui the following year.

American bank architecture underwent an incredible transformation following World War II. As financial institutions nationwide analyzed the need for progressive banking methods, architects responded by radically reinventing the bank’s form.

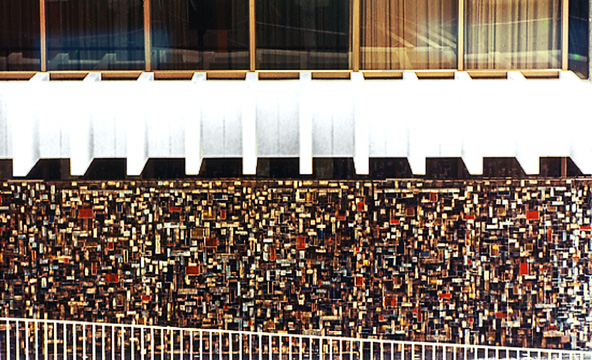

With its bold design, expansive use of glass for transparency, and integrated program of abstract art, the Columbia Savings building was an exceptional example of national postwar banking trends.

Displaying the influence of New Formalism, the building’s modernist form and symmetry represented a reinterpretation of the classically inspired banks of the turn-of-the-twentieth century.

Exceptional signage included two sculptural pylons soaring eighty-five-feet tall. Visible from great distances, their incredible height marked the evolution of building signage in response to Los Angeles’ auto-oriented society.

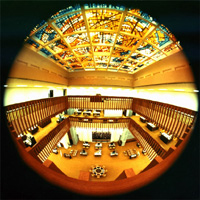

The bank’s design integrated significant works of abstract art, including a 45-foot-long brass screen-waterfall sculptural fountain by local artist Taki and a 1,300-square-foot dalle-de-verre (faceted glass) stained-glass skylight by acclaimed artist Roger Darricarrere that crowned the interior light well. These works were salvaged for sale before the building’s demolition.

Our Position

The Conservancy responded to the project’s environmental impact report (EIR) with detailed information about the building’s significance. Although creative options existed for reusing the building while meeting most of the project objectives, the building’s significance was ignored throughout the environmental review process. The city’s Planning Commission voted on August 13, 2009 to recommend certification of the project EIR.

In an effort to definitively prove the building’s historic significance—and require consideration of preservation alternatives in the EIR—the Conservancy nominated the building for listing in the California Register of Historical Resources.

The nomination was scheduled to be heard in January 2010. The Conservancy urged the city’s Planning and Land Use Management (PLUM) Committee to postpone its vote on the final EIR until the State Historic Resources Commission had a chance to review the nomination. Our plea went unheeded. On December 1, the PLUM Committee voted to recommend certification of the EIR.

The City Council certified the EIR on December 4, 2009. Staff from the Conservancy attended the Council meeting to voice our opposition to the project one last time, as we had for over a year.

Knowing that the certification of the EIR was likely, the Conservancy wrote to the City Council before the meeting, asking for a condition on the certification that would require the issuance of building permits for the new project before allowing demolition of the Columbia Savings Building. This would have safeguarded against the building’s pre-emptive demolition and the very real potential that the site could remain vacant indefinitely, given the current economic climate.

A number of Conservancy supporters and community members also attended the meeting to voice their concerns. Unfortunately, no one had the opportunity to address the Council. The agenda item was quickly voted on with no public discussion, despite speaker request cards submitted at the beginning of the meeting.

Since no public comment was heard, the Council couldn’t consider adding a condition to prevent pre-emptive demolition. As a result, the EIR was certified, the building’s demolition began hours later. The site is now home to a mixed-use residential and retail property.