Place

Los Angeles General Medical Center

Constructed as a monument to modern medicine, the original LA General Medical Center reveals important stories about equity and public health in postwar Southern California.

Place Details

Address

Get directions

Architect

Year

Style

Decade

Designation

Property Type

Government Officials

On Tuesday, December 19, 2023, was a monumental day for a monumental L.A. icon — the 1930s General Hospital — as the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors voted to move forward on a plan to reinvest, adaptively reuse, and reactivate this long-vacant Art Deco landmark in Lincoln Heights. As a public-private development effort, up to 885 new housing units (at least 25% affordable) would be incorporated within the historic building.

The Conservancy was there to speak in support, and we greatly thank Supervisor Hilda Solis and her team for their sustained leadership in making this happen. To put it simply, this is a REALLY big deal, and we are very encouraged to see things moving forward!

In May 2023, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services announced that LAC+USC Medical Center will now be called “Los Angeles General Medical Center.”

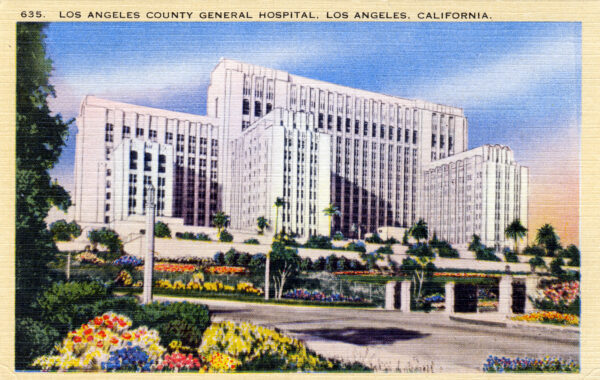

The site of numerous significant events in the history of public health, LA General Medical Center contains one of the city’s most recognizable Art Deco buildings. The facility is located in the Los Angeles’ Lincoln Heights neighborhood and has previously been known as County/USC and Los Angeles County General Hospital.

Made famous to daytime soap opera aficionados with its appearance in the opening credits of General Hospital, the massive Art Deco structure was designed by the Allied Architects’ Association of Los Angeles. The consortium of architects also designed the 1925 Hall of Justice, with input from the County Architect, Karl Muck.

The twenty-story concrete building was constructed between 1927 and 1933, against the backdrop of the Great Depression.

Its design reflects New Deal ideals of scale, centralized organization, and beauty in efficient form.

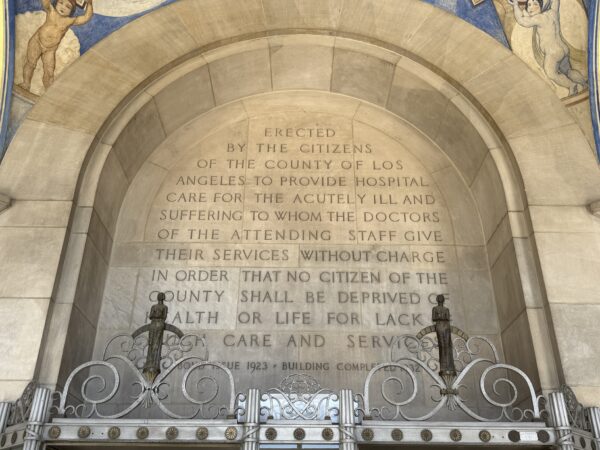

Imposing concrete statues by Salvatore Cartaino Scarpitta overlook the entrance to the building. Occupying the central position is the Angel of Mercy, who comforts an infirm couple. Representations of Western history’s great medical minds—Pasteur, Harvey, Vesalius, Hippocrates, Galen, and Hunter—flank the central figure.

The spacious foyer features exquisite ceiling murals by artist Hugo Ballin of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, and his sons. Ballin also painted the interior of the Los Angeles Times Building and the Griffith Observatory. The saint-like rendering of these figures suggests that an exalted place for the gods of medicine and their earthly instruments.

The sheer size of the entire complex, the largest single hospital facility built west of Chicago, is also a bold architectural statement.

In addition to its architectural significance, the facility is also notable for its relationship to the Chicano Movement of the 1970s and community organizing in response to the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s and ’90s.

Due to the age of the facilities and equipment, as well as new earthquake safety standards for medical buildings, most of the operations of the LA General Medical Center have been relocated to a new adjacent building. The 1933 building has since been converted to office use.