1980-1990: Los Angeles Confirmed

Throughout the 1980s, much of the Los Angeles basin and San Fernando Valley were being built out. Open agricultural land and undeveloped hillsides had once offered a blank slate for development; in the 1980s the emphasis of development shifted to the challenge of infill projects, additions, redevelopment for denser uses, and preservation.

Yet even the dense, clashing mix of architectures in decaying neighborhoods provided inspiration to architects as a manifestation of an unfinished, ever-changing landscape, still rich with possibilities. The minor commercial area of Melrose Avenue and the funky Venice neighborhood were turned into hip neighborhoods, while the Latinx community brought new commercial life to downtown's moribund Broadway.

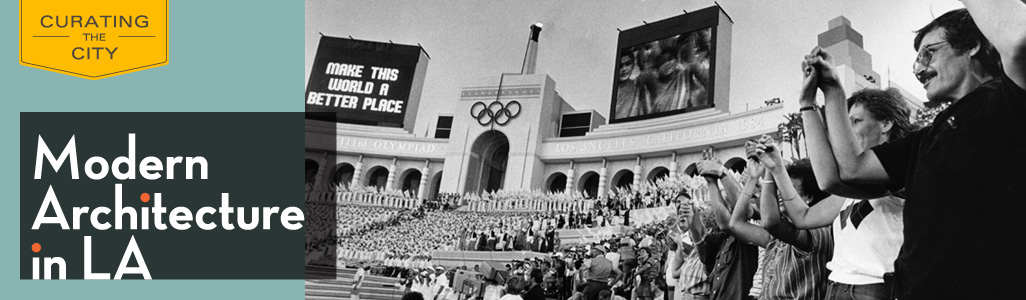

The 1984 Olympics confirmed Los Angeles' rise as a mature global city, as did the growth of immigrant and ethnic communities.

Los Angeles' emergence as a world city had two effects: prominent Los Angeles architects Frank Gehry and Cesar Pelli gained more national and international commissions, while several major local commissions went to architects based elsewhere who were attracted to this new design hub.

These ranged widely; Organic architecture was represented by Oklahoman Bruce Goff’s design with Bart Prince for LACMA's Pavilion for Japanese Art (1988, Miracle Mile); Mexico's Ricardo Legoretta redesigned Pershing Square (1993) in the heart of downtown; Arata Isozaki designed the new Museum of Contemporary Art on Bunker Hill (1986, Downtown); and I. M. Pei designed the prestigious Creative Artists Agency offices (1989) in Beverly Hills. New York's Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer built additions to two major landmarks, LACMA (1986, Miracle Mile) and the Central Library Tom Bradley Wing (1993, Downtown).

At the same time, the dynamic forces of diversity (commerce, popular taste, landscape, climate, and history) in Los Angeles continued to influence design. Planning for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics drew on all of these strengths: spread over the region, the design of these decentralized venues was united by bold, car-scaled supergraphics and installations by Sussman/Prejza and Jon Jerde, a daring innovator in retail architecture.

| St. Matthew's Church (Morre Ruble Yudell, 1983). Photo courtesy Music Guild Online |

Los Angeles' most strikingly original architects, John Lautner, Ray Kappe, Pierre Koenig, and Ed Niles, were active and drawing on their career-long interest in the themes of nature and technology. Though he left L.A. for Texas in 1985, Charles Moore’s influence grew as his office, Moore Ruble Yudell, won public commissions for the Beverly Hills Civic Center (1990) and for St. Matthew's Church in Pacific Palisades (1983). Both were strong assertions of Moore’s ideas of architecture responding to the nature of the place, culture, and human history.

Frank Gehry's career rose to a new level of recognition in the 1980s, even as he continued to draw on the materials and colliding forms of Los Angeles' vernacular landscape and art world for Loyola Law School (1980, Downtown) and the Cabrillo Marine Museum (1981, San Pedro). His exploration of stripped structure and exploded forms contributed to the international trend known as Deconstructivism.

| Loyola Law School (Frank Gehry, 1980). Photo courtesy Architectural Resources Group |

Postmodernism’s influence could be seen in everything from corner mini-malls to highrises. A colorful Postmodern highrise tower in Westwood (1988) by Chicago's Murphy Jahn topped by a crown and striped granite was matched by the dignified Home Savings tower (Kamnitzer Cotton Vreeland and A. C. Martin, 1988, Downtown), a Postmodern highrise with classical symmetry and a chateau's silhouette; it reflected Home Savings architecture's decades-long support for public art and ornament.

Out of this mix of intellectual forces and urban reinvention under the spotlight of international interest, a group of young architects, sometimes known as the Santa Monica, or Los Angeles School, emerged as a vital force in the 1980s. Like Postmodernism, they sought a wider spectrum of sources, and complex compositions suggesting multiple interpretations.

The clashing, colliding, often jarring forms of the vernacular city, the rawness of vernacular materials such as plywood, asphalt shingles, and corrugated metal, inspired their avant garde interpretations of houses and small commercial structures in transitional neighborhoods like Venice, San Pedro, and Culver City.

Allied in part with the Deconstructivist movement that emerged at the end of the 1980s with an exhibit at New York's Museum of Modern Art, the unfinished, in-process, at times apocalyptic imagery of some of their buildings reflected a new vision of Los Angeles, far from the romantic imagery of Helen Hunt Jackson and the arcadian Spanish landscape, or of the Moderne's optimistic futurism.

| Gagosian Art Gallery and Apartments (Studio Works, 1981). Photo courtesy Architectural Resources Group |

Made up of strong individual designers, this group did not share a single vision, however. They ranged from the fragmented sculptural expressionism of Eric Owen Moss, to the intricately mechanistic constructions of Morphosis (Michael Rotondi and Thom Mayne), to the kit-of-parts craftsmanship and pop culture savvy of Studio Works (Craig Hodgetts and Robert Mangurian), to Coy Howard's mechanistic sensuality. Some, like Glenn Small, Frederick Fisher, Thane Roberts, and Frances Offenhauser, focused on sustainable design.

Critic John Chase in 1991 explained this newest blossoming of Los Angeles design as “reflecting the state of flux of a shifting and transitory society....In an era when jump cuts in music videos are de rigueur and surf trunks are made of vivid and clashing panels, it is not surprising that architecture is also designed as a set of contrasting parts.” (Experimental Architecture in Los Angeles, Rizzoli, New York, 1991, p 136.)

Los Angeles' commercial architecture thrived on many levels, from the corner mini-mall to the shopping mall to the commercial strip. In practice, Los Angeles architects have not refused to design commercial buildings in favor of "fine art" designs, and have brought the same quality to both; Frank Gehry designed a World Savings Bank (1982, Toluca Lake), and Morphosis designed the Kate Mantilini restaurant (1986, Beverly Hills).

The tradition of Googie architecture was revived in Grinstein/Daniels' Kentucky Fried Chicken stand (1989, Hollywood), while Paul Essick's Auto Chek Smog Centers (1984, West Los Angeles) combined the exuberant structural expressionism of 1950s car washes with the modular elements of modern technology.

On a larger commercial scale, the shopping mall changed with the times.

The shopping mall, a staple of Southern California design since the 1950s, adapted to new conditions in examples like the sizable Beverly Center Shopping Mall (Welton Becket Associates, 1982, Los Angeles.) While the original malls took advantage of the wide open spaces of newly developing suburban areas by surrounding themselves with surface parking lots, this multi-story mall was built on top of its parking structure, responding to an urban infill site.

Los Angeles’ Jon Jerde redefined the mall at Horton Plaza (1985, San Diego) as a destination including many activities and amenities; his new concepts can be seen at his remodel of the Westside Pavilion (1985, West Los Angeles), a colorful collage of historicized elements with graphics by Sussman/Prejza.

Frank Gehry's Santa Monica Place Mall (1980, Santa Monica) showed his commercial architecture roots and his awareness of LA signage in a multi-story sign of chain link hung on the exterior of the parking structure, while Cesar Pelli's design for Fox Hills Mall (1974, Culver City) walked the line between commercial necessity and taking architectural advantage of natural light and scale.

Preservation found a strong foothold by focusing on L.A.'s Modern history

(including the Moderne or Art Deco) in restorations of the Oviatt and Wiltern buildings, as well as the emergence of the Modern Committee of the Los Angeles Conservancy to focus on postwar Modern architecture.

The Conservancy's volunteer Modern Committee was founded in response to the 1984 demolition of a major Mid-Century Modern landmark of Googie architecture, Ship's Westwood (Martin Stern, Jr., 1958).

Los Angeles' increasing self-awareness continued with the publication of Exterior Decoration by John Chase; California Crazy by Jim Heimann and Rip Georges; Courtyard Housing in Los Angeles by Stefanos Polyzoides, Roger Sherwood, and James Tice; and Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture by Alan Hess.

The story of Los Angeles architecture through the decades is one of ongoing exploration and diverse invention.

Even with intermittent economic setbacks, the region's prosperity continued to fuel new growth and new building. New technologies and growing immigrant populations created ever-changing conditions, but the response of architects has usually been one of innovation, a response to practical functions, and a desire to please, astonish, and delight.

At the same time, a well-established appreciation for the city's vernacular environment has also inspired the region's architects through the decades. These circumstances always provoked varied responses from architects, making diversity a hallmark of the region. This atmosphere continued to attract new generations of talented architects to reinterpret these new conditions.

The wide open spaces still present in the 1940s have disappeared; the freeways have woven the region together more tightly. Los Angeles, however, has continued to be a generator of new ideas, new lifestyles, and new architectures to reflect them.