Place

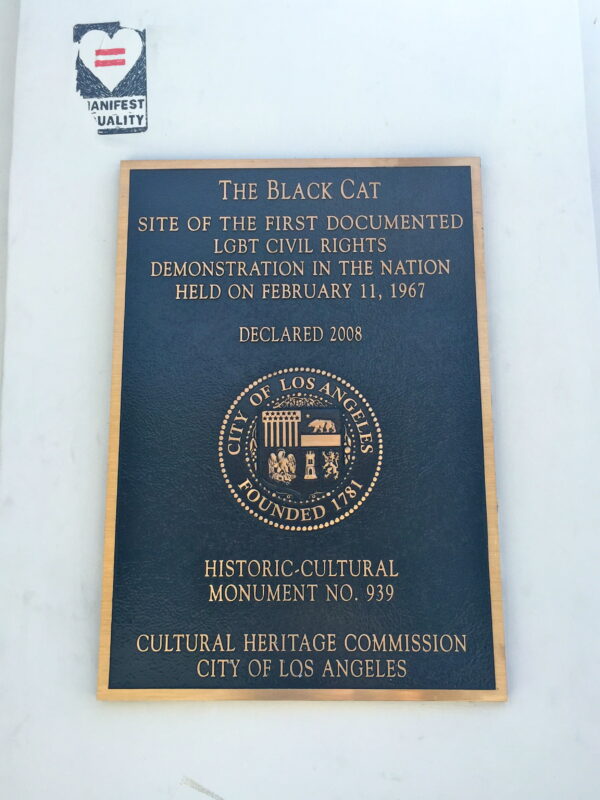

The Black Cat

The site of a 1966 police raid, The Black Cat represents the early evolution of the LGBTQ civil rights movement.

Place Details

Address

Get directions

Architect

Year

Style

Designation

Property Type

Community

https://youtu.be/vs-EeN6ee5E?si=gHfaL14Jm5-SpGe2

Located on Sunset Boulevard, the modest Art Deco building that houses The Black Cat was originally constructed as a Safeway grocery market in 1939, but by the 1960s contained a gay bar and laundromat. The bar attracted a largely working class clientele and was nestled among a number of businesses friendly to gay men and lesbians.

At a New Year’s celebration on January 1, 1967, eight undercover police officers from the LAPD raided the bar just after midnight while patrons were exchanging celebratory kisses and embraces. During the struggle, patrons were beaten and dragged out of the bar and into the street.

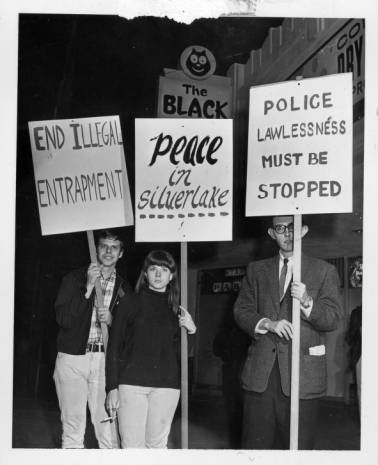

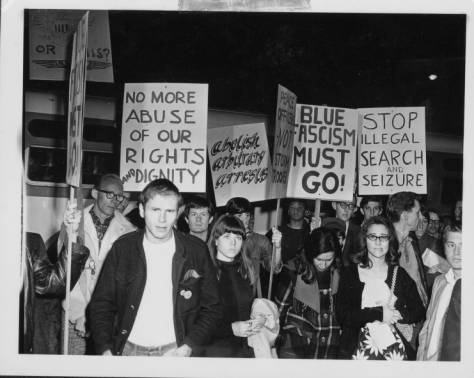

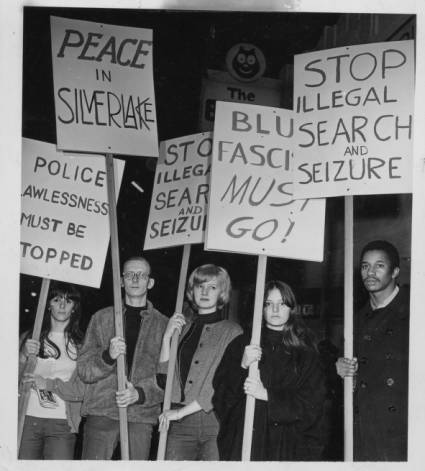

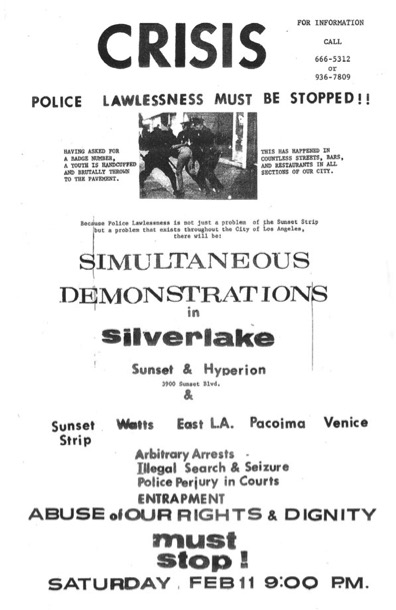

In response to the police raid, activists organized one of the earliest known demonstrations in support of LGBTQ civil rights. Hundreds gathered outside of the bar on February 11, 1967 in peaceful protest of police brutality and discriminatory laws and procedures.

The associated court case related to the baseless lewd conduct allegations of bar patrons from the New Year’s Eve raid is legally significant as the first time in U.S. history that gay men were defended in a court case as equal under the Constitution, though the courts disagreed at the time.

Since the raid and subsequent demonstration, The Black Cat has closed and reopened many times under various names such as the Bushwhacker, Basgo’s Disco, and Le Barcito.

In 2008, The Black Cat was designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument for its early and significant role in the LGBTQ civil rights movement. The building reopened under The Black Cat name in 2012 as a gastropub that primarily caters to a young and diverse clientele.