Blog

Preserving Places with Difficult Histories: Parker Center

February 1, 2017

Not all historic places engender strong positive feelings or associations from the public. Perhaps no place illustrates this better than Parker Center, the 1955 former LAPD headquarters in downtown L.A.’s Civic Center.

Sometimes, a site’s history is so mired in controversial events or personalities that people can’t imagine keeping it. Yet significance can encompass both positive and negative elements in multiple layers of history. Parker Center and other places with such importance can teach us valuable lessons and empower us to face and own the totality of our history – both the good and bad parts.

Efforts to preserve places with difficult histories are not a new idea. For instance, the nearly twenty-year effort to preserve L.A.’s iconic Ambassador Hotel became much more difficult without support from the family of Robert F. Kennedy, who was assassinated there in 1968.

We all know that history is not always pretty. It can be painful and includes some events, actions, and outcomes that we would like to forget. We need to ask ourselves: are we being honest and preserving a place’s full, authentic story, or only the bits and pieces that form our preferred image of history?

Located at 150 North Los Angeles Street in downtown L.A., Parker Center is partly known as the backdrop for television’s long-running Dragnet television series and home to Sergeant Joe Friday. People generally feel good about this association. But other layers of history evoke less nostalgic feelings, from displacement to discrimination. These elements of our history need to be confronted and acknowledged as well.

As Parker Center currently stands vacant in a prime location, some in the City’s administration are calling for its demolition and replacement with a new, nearly thirty-story tower for City office space.

The Conservancy, our Modern Committee, the City’s Cultural Heritage Commission, and others advocate for Parker Center’s preservation and reuse. Soon, the City Council’s Planning and Land Use Management (PLUM) Committee will hear the pending Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) nomination for the building. The full City Council will have until mid-February to decide whether to designate Parker Center as an HCM.

When Parker Center was built in 1955, the eight-story International Style building with integrated art and landscaping components was a significant postwar addition to the Los Angeles Civic Center. Designed by Welton Becket & Associates and J. E. Stanton with a landscape by Ralph E. Cornell, Parker Center was known simply as the Police Facilities Building (renamed in 1966 for Police Chief William H. Parker).

Exemplifying Becket’s “Total Design” philosophy, the building prominently features art installations, including a piece by sculptor Bernard J. Rosenthal and one of the most extensive mosaics ever built, the “Theme Mural of Los Angeles” by Joseph Louis Young. The building’s innovative design, which integrated virtually all departments into a centralized facility, was critically acclaimed at the time as a model for modernizing the police force–as were the state-of-the-art crime labs and communications center. 1956 Popular Mechanics called the Parker Center “the most scientific building ever used by a law-enforcement group.”

By these facts alone, Parker Center’s significance is undeniable. The building has been identified as individually eligible for the California Register of Historic Resources and as a contributor to a National Register-eligible historic district of the Los Angeles Civic Center.

Yet the stories of how Parker Center came to be and what it later symbolized make preserving it all the more challenging and compelling. Before Parker Center, the site contained two of the most vibrant blocks in Little Tokyo. It housed many small mom-and-pop businesses and cultural organizations serving the Japanese-American community. Starting in 1948, the City earmarked these blocks as part of a Civic Center expansion plan and an early form of urban renewal. The site was cleared of all existing buildings—many of which would be considered historic if still standing. The property was remade into a single superblock, with Parker Center’s construction beginning in 1952.

Despite being a federally supported program that ended over forty years ago, urban renewal remains a touchy subject today, especially for preservationists and those personally affected. Thousands of historic buildings and part or all of the neighborhoods, such as Little Tokyo and Bunker Hill, were lost during this era of massive urban redevelopment. Parker Center’s construction was particularly hard felt. In addition to displacing hundreds of Japanese Americans, it spurred feelings that history was repeating itself, as some of these same had been forcibly removed just a decade earlier and confined in World War II internment camps.

Parker Center’s role in telling the story of Little Tokyo’s history is not without controversy. Yet, it is also meaningful, something many do not want to forget or wipe away through demolition.

In September 2014, the Little Tokyo Historical Society joined the Conservancy in urging the City to support a preservation alternative that calls for preserving the central portion of Parker Center while allowing for an expansion at the rear of the site. In recent months, as the Civic Center Master Plan process has gotten underway, the Historical Society has decided to support demolition. Some in the Little Tokyo community call for Parker Center’s destruction as retribution. While understandable, is this a reasonable basis for determining the future of L.A.’s Civic Center? If so, it raises similar and complex questions for other urban renewal areas in L.A. with similar origins and resulted in displacement, including Bunker Hill and Chavez Ravine.

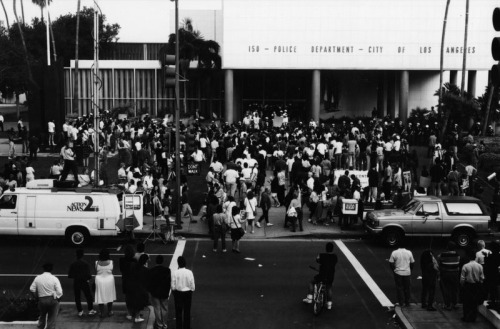

In addition to Parker Center’s early urban renewal roots, its subsequent layers of law enforcement history were not always perceived as positive. William H. Parker oversaw the building’s construction and was one of the most distinguished–and controversial–police chiefs in Los Angeles’ history. During his leadership (1950-1966), he professionalized the police force and developed crime-fighting concepts that are now standard practice. Yet his tenure was also marred with discrimination against the African American and Latino communities; a deep-rooted problem brought into the national spotlight during the 1965 Watts Riots. Even after Parker died in 1966, for many, the building continued to symbolize racial inequalities and police brutality in the City. The most visible example occurred in 1992 when violent protesters surrounded the building following the acquittal of four officers accused of brutally beating Rodney King.

Some argue that it is counter-intuitive, or at the very least ironic, to now want to preserve a place like Parker Center. Yet, without the physical location of these events, it is infinitely harder to tell the stories and demonstrate how far we have come. Parker Center can teach us many things; perhaps it is more relevant than ever in today’s uncertainty.

The fact that Parker Center brings out so many strong feelings only underscores its essential role in Los Angeles’ history and how it helps us remember our past while also allowing us to move forward. In a recent piece about why old buildings matter, Tom Mayes at the National Trust for Historic Preservation wrote, “[t]he history of an old place may be viewed differently over time—and interpreted and reinterpreted as our conception of who we are as a people change.”

The effort to save Parker Center will likely continue to play out over the next month as cases are made for and against preservation and reuse, demolition and new construction, and which approach makes the most sense. That decision comes down to simple facts of dollars and cents, feasibility, and developing creative design solutions. What is not so easy to measure are feelings about a place and deciding whose feelings are more important than others. However, whether these emotions are positive or negative, there should be no question about Parker Center’s significance.