Place

The Factory

The 1929 Factory building embodies a number of significant historical patterns in West Hollywood, from the development of the entertainment industry to the rise of nightlife visibly catering to the gay community.

Saved

The City of West Hollywood approved the proposed hotel and retail development incorporating the historic Factory building, once the headquarters of Mitchell Camera Company and a pioneering gay discotheque in West Hollywood.

Place Details

Address

Architect

Year

Style

Designation

Property Type

Community

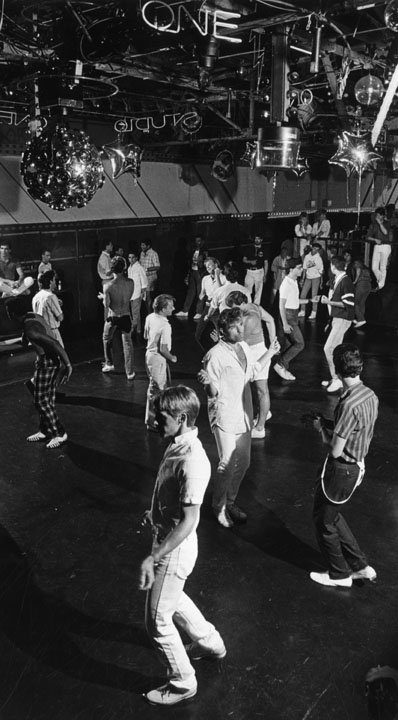

Dancing at Studio One in West Hollywood | Herald-Examiner Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Overview

Important for early Hollywood moviemaking and later for LGBTQ+ associations, The Factory represents layered history and cultural significance, from two separate periods of time. While an industrial building, it helps impart significant stories of both Hollywood and West Hollywood history.

The Conservancy first became involved in July 2014 when developer Faring Capital first announced plans for the Robertson Lane Hotel Project, to redevelop the site and demolish The Factory. Later, following much collaboration with the community and the Conservancy, the project scope was significantly changed and a new redesigned proposal was brought forward that would involve relocating a 140-foot long, two-story portion of The Factory and rehabilitating the exterior. Once completed, the development includes plans for an interpretive program that recognizes the history and significance of the site to Hollywood moviemaking and local LGBTQ+ communities.

About This Place

About This Place

The Mitchell Camera Company, founded in 1919 as the National Motion Picture Repair Company, originally constructed the three-story steel-frame building in 1929 to house manufacturing operations for its motion picture cameras. The 1929 Factory building embodies a number of significant historical patterns in West Hollywood, from the development of the entertainment industry to the rise of nightlife visibly catering to the gay community.

It was one of many companies to establish production facilities in close proximity to Hollywood film studios at this time. For decades, Mitchell cameras were the mainstays of Hollywood studios.

During that time, Mitchell cameras could be found in nearly every Hollywood studio, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recognized the company more than once for its technical achievements.

The 1929 Factory building embodies a number of significant historical patterns in West Hollywood, from the development of the entertainment industry to the rise of nightlife visibly catering to the gay community.

In 1941, Mitchell Camera Company expanded the western side of the factory building in order to increase production capacity. With the onset of World War II, many of the country’s manufacturing operations were redirected towards the war effort, and, by some accounts, the Mitchell Camera factory may have played a significant role in developing new military technology, including bombsights used in aircraft.

Mitchell Camera Company remained in West Hollywood until 1946, when it relocated its operations to a factory in Glendale. Following the move, the West Hollywood factory building was converted to a military salvage depot and, later, a furniture factory.

The building functioned as Mitchell Camera Company’s production facility until 1946, when the company relocated its operations to Glendale. During that time, Mitchell cameras could be found in nearly every Hollywood studio, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recognized the company more than once for its technical achievements.

The Era of The Factory and Studio One

The building first became a nightclub in 1967, with owner Ron Buck converting the cavernous space into the high-profile, private establishment known as The Factory. The club featured multiple performance stages and four rooms reminiscent of movie sets, divided by repurposed stained glass windows, and guests sat on an array of furniture, including recycled church pews. From 1967 to 1972, the building operated as The Factory, an invitation-only nightclub that was the favorite of Hollywood celebrities. Several years later, at the height of the disco era, the building was transformed a second time into an exuberant dance club for West Hollywood’s gay community.

Until its closure in 1972, The Factory was the place to be seen. In 1974, the building was transformed into a thriving discotheque. Known as Studio One, the glamorous dance club specifically catered to West Hollywood’s visible gay community and remained in operation until 1988.

Architect, attorney, and artist Ron Buck purchased the building in 1967 and transformed it into an exclusive, invitation-only nightclub, naming it The Factory. It quickly earned a loyal following of A-list guests, who were attracted to the live entertainment, gourmet food, and exuberant décor. Buck also converted the lower floor into an art gallery, which has since seen a range of uses, including a cabaret theater and a hardware store.

Despite its initial popularity, interest in The Factory had faded by the early 1970s, causing the club to close its doors in 1972. Over the next several years, the building was home to a series of new tenants before reopening as Studio One in 1974, a transformative discotheque within West Hollywood’s gay community. Owner Scott Forbes, a Beverly Hills optometrist turned party promoter, envisioned the club as a visible hub in the heart of the community. Known as Studio One, the club served as a visible social hub for many gay men. Its renown within the community made it an important hub for activism and fundraising when the AIDS epidemic struck in the early 1980s. And, taken with places like Circus Disco and Jewel’s Catch One, it tells a critical story about race, class, gender, and sexual identity in Los Angeles.

Debuting at the height of the disco era, Studio One was open seven days a week and reflected national trends in nightlife and entertainment.

Studio One remained in operation until 1988 and was widely recognized during its tenure in the former camera factory as one of the most successful discotheques in the United States. Since the business’s closure, the building at 661 North Robertson Boulevard has continued to function as a nightclub.

From its early years as one of the backbones of the motion picture industry to its later turn as a significant cultural anchor in the local gay community, the history of The Factory building has been one of transformation.

With the rising popularity of disco in the early ’70s, Scott Forbes’ venture into West Hollywood’s nightlife with Studio One was a runaway success in the gay community. The disco scene first emerged within the context of New York’s gay bar subculture, and dance clubs quickly appeared in cities throughout the U.S.

Unlike many of its counterparts, Studio One specifically targeted West Hollywood’s visible gay community.

Forbes told the Los Angeles Times in 1976, “Studio One was planned, designed and conceived for gay people, gay male people…Any straight people here are guests of the gay community. This is gay!”

Studio One, however, did not openly embrace the entire LGBTQ community in Los Angeles, and Forbes was criticized for his exclusionary policies against women and people of color. Non-white patrons often asked for multiple forms of identification, which effectively barred them from entry. The Gay Community Mobilization Committee organized protests in front of the club in the mid-1970s in response to these discriminatory practices.

These actions directly contributed to the rise of other establishments such as Circus Disco and Jewel’s Catch One, which openly welcomed and fostered a diverse clientele. Taken together, these places tell a critical story about the complexities of race, gender, class, and sexual identity in Los Angeles’ built environment.

Its name a nod to its Hollywood history, the club could accommodate up to 1,000 guests, who were drawn in each night by the glamorous mirrored disco balls, elaborate sound and lighting systems (including the use of strobe lights, neon, and lasers), and the always-packed dance floor.

Our Position

In March 2019, developer Faring Capital proposed modifications to the Robertson Lane Hotel project. After several years of working closely with the developer of the Robertson Lane Project, we are pleased that the final plan will result in greater preservation of The Factory building, including retention of an additional four, 20-foot modules of the building. Rather than 55%, as in the previously approved project, 92% of the building’s existing length and nearly 80% of the entire building will be preserved.

Another modification removes a vehicular driveway that was previously proposed as penetrating The Factory. An additional 42-foot buffer between The Factory’s south elevation and the neighboring building to the south will be provided. This will create functional space to program and experience the south elevation and former La Peer Drive facade and entrance to Studio One.

Together, we found a way to strike a balance between old and new. The Conservancy supported these project modifications at a June 2019 meeting of West Hollywood’s Historic Preservation Commission, and the Commission approved the newly proposed changes.

We are very pleased that more of this building with important LGBTQ and early Hollywood production history will be saved and incorporated into the new project.

In July 2016, developer Faring Capital announced plans to retain and incorporate most of the historic Factory building into its proposed Robertson Lane Hotel Project. The redesigned proposal would involve relocating a 140-foot long, two-story portion of The Factory and rehabilitating the exterior. Once completed, the development would include an interpretive program that recognizes the history and significance of the site to local LGBTQ communities.

The Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the proposed project was released in March 2017. The Conservancy submitted written comments in support of the proposed project, including its partial preservation approach and thoughtful mitigation measures in May 2017.

We appreciate the project team’s willingness to work with the preservation community on a project that strikes a balance between old and new and offers a meaningful path for interpreting and commemorating the site’s history. Click on the tab “Our Position” to learn more.

When the project was first announced, it called for the demolition of the 1929 Factory building at 661 North Robertson Boulevard, among other structures on the site.

In the spring of 2016, the West Hollywood Heritage Project nominated The Factory for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Though the State Historical Resources Commission initially turned down the request in July 2016, the advocates resubmitted the nomination with new information about the property’s significance. The Commission reviewed the revised nomination on October 28 and voted to recommend designation.

The property was listed in the California Register of Historical Resources, and the National Park Service determined that it was eligible for the National Register in February 2017.

On June 24, 2015, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named The Factory to its list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places in recognition of the growing threat to this icon of the early entertainment industry and West Hollywood’s pioneering gay community. This year’s list represents the most diverse selection of stories and places to date.

Says Stephanie Meeks, president of the National Trust:

“The Factory is a trove of important and multi-layered history that simply cannot be replaced.”

A Facebook group called Save The Factory West Hollywood was formed to help build support and awareness. The West Hollywood Preservation Alliance also expressed concern about the proposed project and demolition of The Factory.

Role of L.A. Conservancy

The Conservancy is pleased that the building at 661 North Robertson Boulevard is now listed in the California Register of Historical Resources and has been determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places for its associations with the motion picture industry and West Hollywood’s pioneering gay community.

Since the Robertson Lane Hotel Project was first annouced with full demolition proposed, the Conservancy has been working to ensure a meaningful preservation outcome for The Factory. What has developed and evolved following many discussions is a reimagined project that provides a unique opportunity to create a dynamic and walkable urban center with a mix of building heights and styles of both historic and new construction.

As an example of adaptive reuse, The Factory building is now envisioned as a core, highly visible feature of the proposed project. To achieve this goal, the project calls for the dismantling, truncating, relocation, and rehabilitation of a substantial portion of the industrial building, as a partial preservation approach.

The Conservancy approaches every preservation issue and project as a case-by-case scenario, each with unique circumstances. Our preference is always for the full preservation and retention of a historic resource and minimizing impacts wherever possible.

The Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) studied a range of potential impacts to the historic building that could result from the proposed project and includes a robust package of mitigation measures. As proposed, a portion of The Factory is intended to be preserved, though essentially reconstituted as a smaller structure than currently exists and at a different orientation on site.

The Conservancy has analyzed this issue and pressed for retention of as much of the original building as possible. In this case, we believe the proposed partial preservation project is meaningful and achieves a preservation outcome, especially when combined with the suggested package of mitigation measures.

Unlike many other buildings, The Factory features modular construction, which is often erected in various sizes and shapes and/or dismantled and rebuilt elsewhere. This is an important and contributing factor to the partial preservation decision, and the remaining building will be nearly identical in appearance.

In addition to the building’s preservation, the Conservancy advocated for the inclusion of meaningful site interpretation as part of the project’s mitigation. Given the complexity of The Factory’s social and cultural history—including patterns of racial and gender discrimination—we strongly believe that all interpretation and commemoration of the building’s history should reflect a diverse range of perspectives within local LGBTQ communities.

Overall, we feel the mitigation measures are thoughtful and will allow a diverse public to access, experience, and understand The Factory building in a way that is not possible today.

Click here to read the Conservancy’s 2017 letter on the Draft EIR