Place

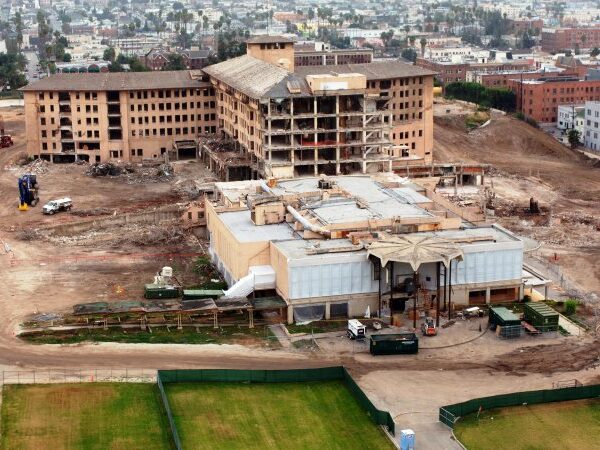

Mole-Richardson Studio Depot (Demolished)

A prominent fixture along the La Brea Avenue commercial corridor, the Mole-Richardson Studio Depot featured a proportionate blending of Zigzag and Classical Moderne detailing.

Lost

A prominent fixture along the La Brea Avenue commercial corridor, The demolition of Mole-Richardson Studio Depot in June 2014, helped lead to the approval of the Los Angeles Demolition Notification Ordinance.

Place Details

Address

Architect

Neighborhood

Year

Style

Decade

Property Type

Government Officials

Community

Photo by Adrian Scott Fine/L.A. Conservancy

Overview

The former Mole-Richardson Studio Depot at 900 North La Brea Avenue was designed by master architects Morgan, Walls, and Clements. Completed in 1930 as the home of Moderncraft Laundry Company, the building most recently served as a studio supply retail store operated by the Mole-Richardson Company.

The Mole-Richardson building featured a mix of Zigzag and Classical Moderne detailing, including intricate, chevron-patterned grillwork, and represented the evolution of the Art Deco architectural style in Los Angeles. Although its central pylon tower had been removed long ago, the building retained a high degree of original design integrity.

In June 2014, the property owner demolished the building without prior public notification or review by the Los Angeles Office of Historic Resources.

About This Place

About This Place

Morgan, Walls, and Clements were a prolific local architectural firm known for their theater designs and commercial work from the 1920s and 30s, though the firm’s lineage spanned from 1864 to 2006 and operated under a variety of names.

The principals were Octavius Morgan, J.A. Walls, and Stiles O. Clements. The firm was responsible for the design of many notable structures, including numerous significant Art Deco designs that helped advance that architectural style in the region. These include the former Richfield Building (1928, demolished), the Dominguez-Wilshire Building (1930), and the Pellisier Building and Wiltern Theatre (1931).

As proposed, the 904 La Brea Project would demolish two more buildings – 926 and 932 North La Brea Avenue – and construct a new seven-story mixed-use building in their place. The Mitigated Negative Declaration (MND) for the project does not acknowledge that the Mole-Richardson Building was demolished at the site prior to the October 2014 submission of the proposed project. Given the short timeframe, it is logical to conclude that a project of this scope was not only anticipated, but was, in fact, known at the time of demolition.

In addition, the MND did not acknowledge that there may be an additional historic resource located on the project site. According to research conducted by Hollywood Heritage, the building at 932 North La Brea housed the Dunning Process Co. from 1931 to 1955, which devised the revolutionary “dunning film process.” This was a special effect that created a traveling matte background process shot for motion pictures. It simplified scenes from driving to flying, allowing stock footage or previously shot second unit work to be combined in shots featuring a film’s stars. King Kong is just one example of the many classic motion pictures to employ this process.

Our Position

The Conservancy is very concerned about the precedent that the 904 La Brea Project might set regarding the treatment of an identified historic resource and its adherence to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Because the Mole-Richardson Building had been previously identified as being eligible for the local, California, and National Register, its demolition resulted in a significant impact where an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) was required.

The preemptive demolition of an historic building prior to project submission represents a flagrant abuse of CEQA, the very purpose of which is to avoid or minimize adverse impacts to the extent feasible by examining alternative approaches to a project.

Because the building was not landmarked and a replacement project was not yet known, the property owner was able to obtain the proper permits without public notice or review by the Los Angeles Office of Historic Resources. The Mitigated Negative Declaration (MND) for the replacement project (904 La Brea Project) was released in January 2015.

On April 9, the City Planning Commission recommended approval of the proposed project and MND, with a condition that the applicant meet to discuss possible mitigation measures with Council District 4, the Conservancy, and Hollywood Heritage prior to this going before the City Council’s Planning and Land Use Management (PLUM) committee.

The application for the demolition permit was submitted on April 10, and the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety issued the demolition permit five days later. At that time, the City did not have a requirement for public notice of demolitions, so the community was unaware of the plans until construction activity was underway.

As one of several high-profile demolitions in recent years, the loss of the Mole-Richardson Studio Depot helped spur the passage of the new Demolition Notification Ordinance in the City of Los Angeles. It also represents a growing trend in the City of issuing MNDs in lieu of full Environmental Impact Reports (EIRs), despite the presence of known historic resources.

In November 2014, following the demolition of the Mole-Richardson Building, the Los Angeles City Council approved Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell’s August 2013 motion to create new legislation that would empower community members to prevent surprise demolitions of unprotected historic buildings. The Conservancy worked closely with Councilmember O’Farrell’s office to help shape the legislation.

Before demolition permits can be issued for buildings older than forty-five years, the new Demolition Notification Ordinance requires property owners to inform abutting neighbors and their Councilmember’s office of any planned demolition activity. A public notice must also be posted on the property.

The ordinance creates a thirty-day window for stakeholders to potentially negotiate preservation alternatives if a significant historic property is affected. This might include nominating it for Historic-Cultural Monument status. The ordinance also introduces a sixty-dollar fee to cover administrative costs.