Resolved

1968 East L.A. Chicano Student Walkouts (Blowouts)

On June 26, 2018, the National Trust for Historic Preservation placed the "Walkout Schools of Los Angeles" on America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list. Exposure at the national level heightened the awareness of these threatened sites.

Resolved

Issues that may have resulted in imperfect outcomes, but still display significant progress

Overview

On June 26, 2018, the National Trust for Historic Preservation placed the “Walkout Schools of Los Angeles” on America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list. Exposure at the national level heightened the awareness of these threatened sites. Despite community concerns, Roosevelt High’s iconic R Building and Auditorium were demolished as part of LAUSD’s Comprehensive Modernization Program in 2019. With few intact examples left to tell the story of the historic 1968 Chicanx students’ fight for educational equity, the Conservancy is encouraged by LAUSD’s preservation-minded approach to the proposed modernization at Lincoln High School.

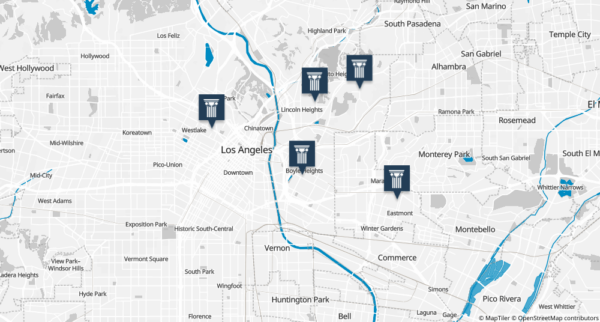

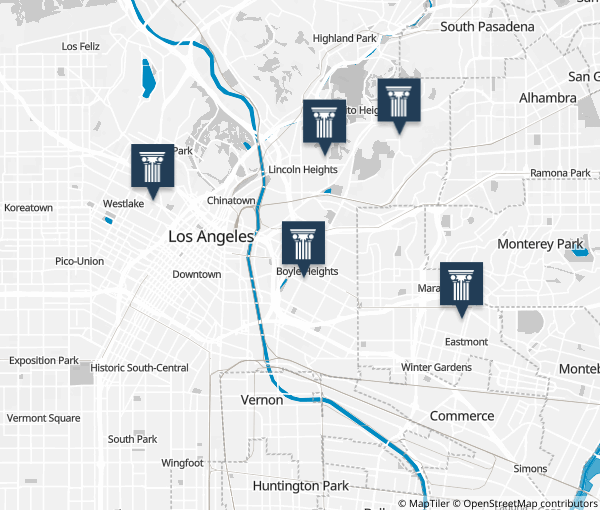

In March 1968, students from Woodrow Wilson High School (now El Sereno Middle School), James A. Garfield High School, Theodore Roosevelt High School, Abraham Lincoln High School, and Belmont High School—all of which had populations made up of more than 75 percent Latinx students—organized and led a series of mass walkouts to demand educational equality within the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD).

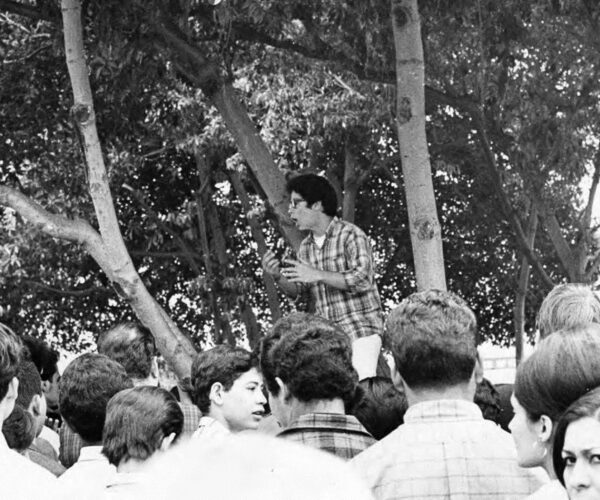

Known as the East L.A. Chicano Student Walkouts or Blowouts, the protests voiced concerns over run-down campuses, overcrowding, corporal punishment, lack of college prep and culturally relevant courses, and teachers who were poorly trained, indifferent, or racist. During the Walkouts, many student protesters were blocked by administrators barring doors to the outside, and others were violently jailed by helmeted police officers.

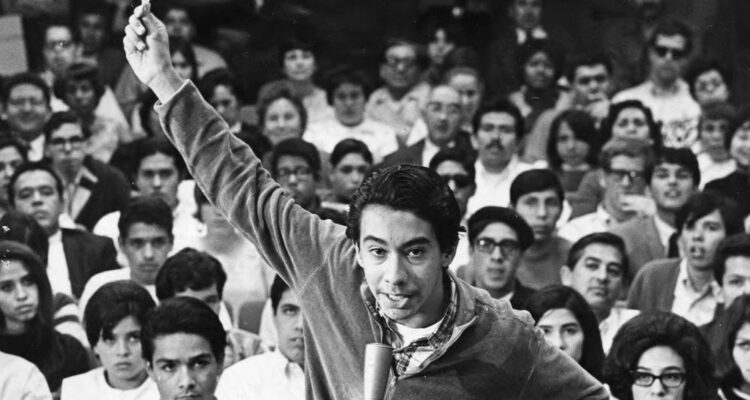

Peaking at 22,000 students, and serving as an early catalyst of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, the Walkouts are considered among the first major Mexican American opposition to racial and educational inequality in the U.S.

The actions led to the school district hiring more Latinx teachers, and the introduction of bilingual classes and ethnic studies. Partly as a result, the following year, the number of Mexican-American students enrolling at UCLA rose 1,800 percent.

March 6, 2018, marked the fiftieth anniversary of the East L.A. Chicano Student Walkouts. Fifty years later, the historic high schools remain important neighborhood anchors for some of the oldest and most ethnically diverse neighborhoods of Los Angeles and in the nation. They also serve as collective reminders of the ongoing need for change through student-led activism. Then, as now, high school students were angry and frustrated that the institutions that were supposed to support and protect them were falling short.

On June 26, 2018, the National Trust for Historic Preservation placed the “Walkout Schools of Los Angeles” on America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list.

About This Issue

Although it’s difficult to trace the origins of the East L.A. Chicano Student Walkouts (Blowouts) to one particular event, group, or person, the Mexican American Youth Leadership Conferences for high school students held at Camp Hess Kramer were certainly influential in inspiring youth to identify and work for social justice. Hundreds of Mexican-American student leaders gathered at the annual conferences, which were intended to promote citizenship but also became forums for discussing problems at schools.

In 1963, Sal Castro had just begun his teaching career at Belmont High and volunteered at the conference. There he found hundreds of students from all over L.A. County who expressed similar grievances about poor conditions in the schools and lack of opportunity for Mexican-American students. At the time, dropout rates for Mexican-American students in East L.A. were among the highest in the nation: 45 percent at Roosevelt, 57 percent at Garfield, 39 percent at Lincoln, and 35 percent at Belmont.

In 1967, Time magazine’s “Minorities: Pocho’s Progress” described “the bleak barrios” of East L.A. as full of “rollicking cantinas with the reek of cheap red wine and greasy taco stands and the rat-tattat of low-riding cars down the avenue.” Castro, who was born in the Eastside neighborhood of Boyle Heights, was enraged that his community was viewed in this negative way and began organizing meetings with high school students from the Eastside, including Lincoln High, where he taught.

The term “Blowout” was coined by John Ortiz, a Mexican-American student at Garfield High actively involved in the Walkouts. Recalling its origin in a 2010 interview, he said, “The term ‘blowout’ was like an Eastside hipster term; it was a jazz expression. It meant being expressive – you would say of a musician, ‘He blew it out.’ I improvised using the term to refer to the walkouts. The other kids picked it up, as did the Chicano media.”

A Blowout Committee was formed at four East L.A. schools (Roosevelt, Lincoln, Garfield, and Wilson), and another committee included students from all four schools. Belmont High was not technically in the Eastside, nor was it among the original four schools that organized the Walkouts. Belmont had a lower percentage of Mexican-American students, but they formed their own Blowout Committee soon after and walked out on March 8, along with other schools. The result was what some called the “Mexican-American revolution of 1968” and La Raza newspaper referred to 1968 as the “Year of Decision.”

From March 1 to March 8, 1968, approximately 22,000 students at five LAUSD schools in East L.A. and near Downtown walked out of their classrooms to protest run-down schools, overcrowding, lack of college prep and culturally-relevant courses, among other grievances. School administrators and police officers were inconsistent in their responses. Lincoln High students were allowed to leave the school grounds peacefully, while at Roosevelt High, administrators locked the gates and LAPD squad cars surrounded the campus to intimidate students.

A special meeting of the LAUSD board was held on March 11, 1968, where student body representatives from the Blowout schools and those who walked out in solidarity spoke presented a list of student demands to the Board. On March 26, another special Board meeting was held at Lincoln High’s Auditorium, where the Board presented their responses to the students’ demands to a packed audience. Thirteen people, later called the East L.A. 13, including Lincoln High teacher Sal Castro, were indicted by the County Grand Jury a few months after the Walkouts. Charged with conspiracy for their involvement in the demonstrations, the organizers faced a total of 66 years in prison if found guilty. Castro would be fired from his teaching job after the Walkouts, but fought successfully to be reinstated. The California State Appellate Court struck down the charges two years later.

“It was a definite break with the past,” writes historian Rudy Acuña of the 1968 Walkouts. “Before the walkouts, all through the civil rights movement, people said Chicanos didn’t do things the way the blacks did. But when they saw the results of the blowouts, there was no turning back”. Dr. Julian Nava, a member of the Board of Education during the Walkouts (and Roosevelt High alum), reflected “[t]he schools will not be the same hereafter.”

Many of the high school and college student organizers went on to live lives of accomplishment. Paula Crisostomo, a Lincoln High student, became a school administrator where she continues to fight for reform in education. Roosevelt High alumna Victoria Castro was elected to the LAUSD Board, where she served as president from 1998 to 2001. Lincoln High alumnus Moctesuma Esparza became a successful film producer and remains an activist by creating opportunities for Chicanos in entertainment and in other fields. Garfield High student Harry Gamboa, Jr. became an artist and writer. Carlos Muñoz, Jr., one of the East L.A. 13, went on to a distinguished teaching and research career in the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

Our Position

The Conservancy recognizes the East L.A. Chicano Student Walkouts’ importance to Chicanx and Latinx history. The courage and determination demonstrated by students in 1968 served as a catalyst for the Chicano civil rights movement in Los Angeles and beyond. Scholars with the Hispanic Access Foundation recently identified Lincoln High School in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles as one of ten places associated with Latinx heritage warranting recognition and protection.

The National Park Service’s 2013 American Latino Theme Study similarly highlighted places associated with the Walkouts in their broader history of Latinx history. Preserving the Eastside school sites and other places associated with the Walkouts provide a deeper understanding of the interrelated histories and experiences of Chicanx across the city and the nation at large. Doing so also affirms that these important events in the Latinx experience in Los Angeles is American history.

Despite widespread support for a preservation alternative, on May 8, 2018, the Board of Education of the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) voted to adopt the Final Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the Roosevelt High School Comprehensive Modernization Project and approve a plan to demolish Roosevelt High’s original Auditorium and Classroom Building (1922), also known as the R Building, as well as other buildings on campus that comprise a National Register-eligible historic district significant for its association with the 1968 Walkouts.

The Conservancy has partnered with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and other community organizations, including the grassroots Committee to Defend Roosevelt, to raise awareness of demolition threats to the remaining Walkout Schools. The Los Angeles Conservancy and partners, as well as California State Assembly member Wendy Carrillo and City of Los Angeles Council member Gil Cedillo, strongly believe that LAUSD can provide quality education, state-of-the-art facilities, and historic preservation—it’s not an “either/or” choice.

The schools should be modernized, but it doesn’t need to happen at the expense of the Eastside community’s unique history and sense of identity. Preservation allows a lot of flexibility in adapting buildings to continue serving the community. Rehabilitation of historic building interiors can range from preserving existing features and spaces to total reconfigurations to meet new service and safety needs. As an example, LAUSD has already upgraded older buildings at other campuses, including David Starr Jordan High School in South Los Angeles and is currently planning to do so at John Burroughs Middle School in Hancock Park. Often, the greenest and most cost-efficient building is the one that’s already built.

How You Can Help

If you would like to stay informed about Lincoln High School’s Comprehensive Modernization Project, contact M. Rosalind Sagara, Neighborhood Outreach Coordinator.

Timeline

Issue Resources

- "East L.A. Blowouts: Walking Out for Justice in the Classrooms," KCET, March 7, 2018

- "East L.A., 1968: ‘Walkout!’ The day high school students helped ignite the Chicano power movement," LA Times, March 1, 2018

- "1968: How a year of tumultuous events continues to shape our world," Los Angeles Times, March 1, 2018